My speech at the State Library of Victoria for the launch of

Carmel Bird Digital Literary Award 2017

If you think it’s a bit funny for me to be launching a writing competition named after me, let me tell you, that’s only half of it. I am also judging the competition. With a bit of luck I might win it. It’s probably called solipsism.

Before I describe the competition, I’ll give you the history, explaining how such a thing could have come about. In 2011, when Bronwyn Mehan was in the early years of her publishing company Spineless Wonders, she sent me an email asking me if I would consider her naming a writing competition in my honour. I considered it. So first there was the Carmel Bird Short Story Competition.

I followed the fortunes of Spineless Wonders, until, in 2013, I realised Bronwyn had a certain expertise that I needed. Here’s the history of what I needed, and why.

Back in 1997 – yes – twenty years ago – I started my website. This was in fact the first writer’s website in Australia. So people could be forgiven for imagining I was a writer who was across a certain amount of electronic publishing. I was invited, in 2013, to contribute an essay to an online site where they were talking about how writers use technology. I didn’t really know much to write about, but I was at the time thinking about the electronic publication of my old book Dear Writer, and so I wrote an essay that was in fact a BIT OF A fantasy. The essay concluded at the point where I said I was going to make an ebook of Dear Writer. I thought I got away with that – but no – the editor of the site requested a second part to the essay, the part in which I described the making of the ebook. Hmmmm.

By this time I had bought my own fantasy. So I started making an ebook. I did? Dear Audience, I was incapable of doing the first thing about making an ebook.

But wait – in an apartment with a roof garden in Sydney (true) there was the industrious genius Bronwyn Mehan. She would know how to do it. So – and now I must cut a pretty long story short – Bronwyn took over the making of the ebook of Dear Writer – called Dear Writer Revisited – and I was able to write part two of the essay and everybody was happy. Specially me. Spineless Wonders also published Dear Writer Revisited as a paperback.

Time passes.

The Carmel Bird Short Story Competition keeps happening.

Then, in 2017 Bronwyn devised the notion of having ebook publication as the prize. And hence you now have the CB Digital Literary Award. That’s what I am actually launching at this minute.

So now I will give you some facts (everything I just said was true – but this next bit is more important). These facts can also be found on the postcard.

Here’s what you do.

You write up to 30,000 words. What sort to words? Well this award is open to traditional short fiction, whatever that may be, to quote the Prince of Wales – but open also to microfiction, novellas, graphic novels, verse novels, experimental thingies. Go wild. And you know how it is fashionable to write an exegesis on your fiction, and get a PhD? Well if you wish you can incorporate such a thing into your submission – within the word limit. You might not get a PhD. My hard copy collection of stories, also published by Spineless Wonders – the title is My Hearts Are Your Hearts – has such a thing within its pages.

You submit your work electronically with various supporting documentation by APRIL 30 2018

The next bit will go in one ear and out the other, but the notes are on the handy postcard.

I will select a long list by the beginning of June (fast reader) and writers on the long list will be notified by email. The long list will also be announced on the SLV website and the SW website.

The three finalists will be announced in July.

There will be an award ceremony in August.

The outright winner will have the work published as an ebook in December 2018.

And here is the punch line:

The winner will receive $3000 in prize money, and the two runners up will each receive $1000. Now THAT bit might make you sit up and take notice.

The two runners up will also have their work published as ebooks in due course. All the ebooks will be part of the SW Capsule Collection – of which The Dead Aviatrix is the first volume.

The Capsule Collection is an initiative of that bold and creative publisher, Spineless Wonders. It is not always a simple matter for a writer of short stories to have a collection published in hard copy, and to have the opportunity to send a collection into the ether so that readers can access it any old time on their phones – that is a distinct boost to the life and development of short fiction. And of course if your work is published in the Capsule Collection, there is nothing to stop you from adding more stories or whatever, and having a much larger volume published in hard copy by some other publisher.

You will have questions about all this – and Bronwyn can best answer those. I am just launching the competition on its merry way.

And while we are talking about skill and luck – I would like you to take out your little blue door prize tickets and see who among you wins a packet of Blue Heaven Aeroplane Jelly Crystals. Andy Griffiths has kindly agreed to draw the winners in a minute.

If you have ever been a student at one of my workshops, you will know that each workshop is a mini writing competition with me as the judge. The prize there is not publication but the Silver Eggcup. Students have to guess what qualities I am looking for in the winning stories. It’s more or less the same here. The point is that you the writer write something that convinces me the judge that the writing is worth reading. So that’s all there is to it really. It’s as easy as it sounds. A little quote from Dear Writer Revisited:

‘If you write stories, you write stories – that is what you do. Get on with it.’ Launch Over. Now for the door prizes. Here comes Andy.

(speech by Carmel Bird, December 2017)

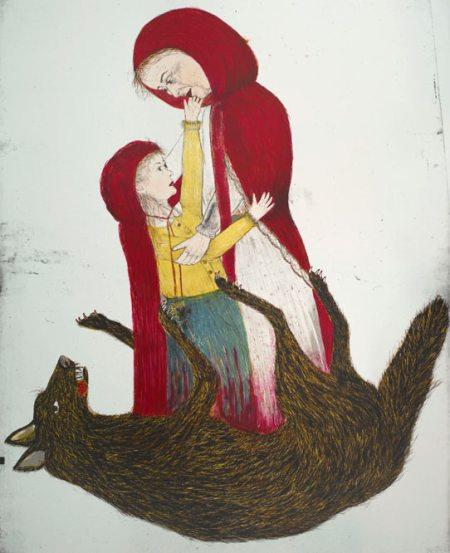

Image by Kiki Smith

Image by Kiki Smith